Using Paper Checkers Responsibly

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource gives a general sense of how so-called “paper checker” applications work and provides best practices for their use. See also our similar article on citation generators.

Introduction

If you’ve used a word processor in the past several decades, you are probably already very familiar with the idea of a “spell checker.” This, of course, is a feature of a program that notifies you when you type a misspelled word. Spell checkers make life easier for writers by reducing the time they need to spend re-reading their work for typos. They are such handy labor-saving tools that we now tend to take them for granted, despite the fact that they can occasionally make mistakes (for instance, by flagging a foreign word as improperly-spelled). Most writers simply understand that the editorial input a spell checker provides must be secondary the author's own judgment.

Recently, “paper checker” applications that tout features far beyond basic spell checking have emerged. Most at least provide sentence-by-sentence grammar feedback. Some apps even boast the ability to pinpoint tricky voice and style concerns (like, for instance, inappropriate use of the passive voice) and give on-the-fly suggestions for improvement. These powerful new features make the author's oversight even more important. Used judiciously, paper checkers can make the work of revision quicker and easier than ever before. Used carelessly, however, they can become crutches that narrow writers' horizons, prevent true growth, and even sometimes introduce new errors.

In short, like spell checkers, paper checkers work best when their advice is secondary to the author's own judgment. For this reason, the “best practice” guidance in this resource is intended to help you exercise your judgment if you choose to use a paper checker app.

How Do Paper Checkers Work?

Like most digital products, paper checker apps vary greatly in their quality, reliability, and sophistication. Some apps perform both very simple functions (like checking for spelling errors) and complex functions (like looking for sentence structure errors) as they review your paper.

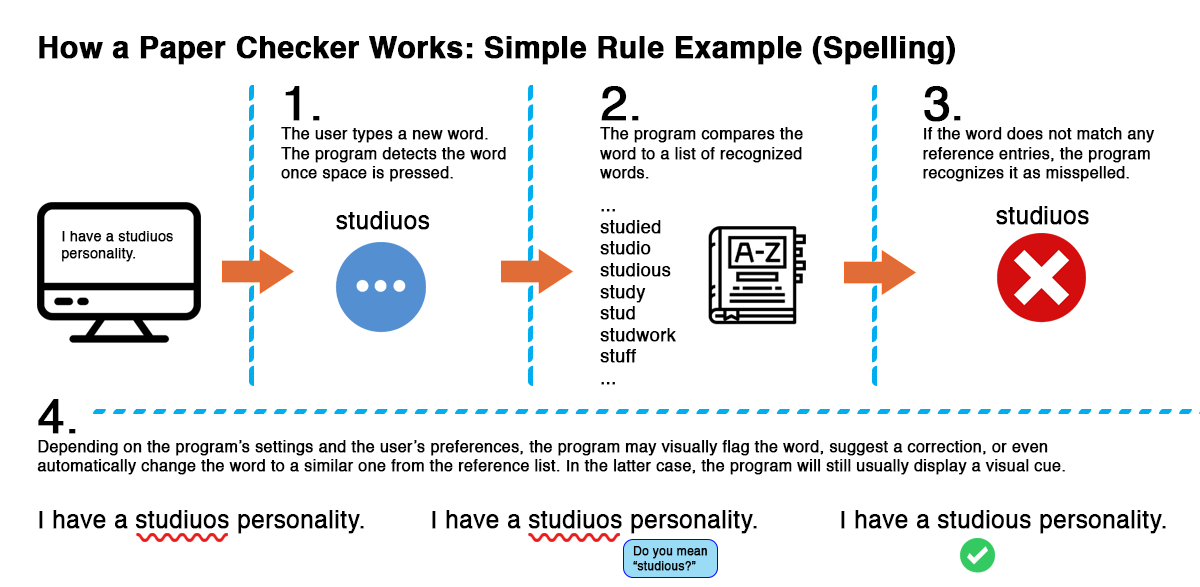

Paper checkers’ simpler functions usually operate according to rote systems of rules. For example, they may catch spelling errors by comparing each word in the paper to a large database of recognized words. Any word that does not match a word in the database can be quickly flagged as misspelled. They may catch simple grammatical errors via similar rules: a rule that periods must precede (and not follow) an ending quotation mark, for example, would help the app catch improperly-formatted quotations.

The diagram below illustrates how a paper checker handles a simple task: spell-checking.

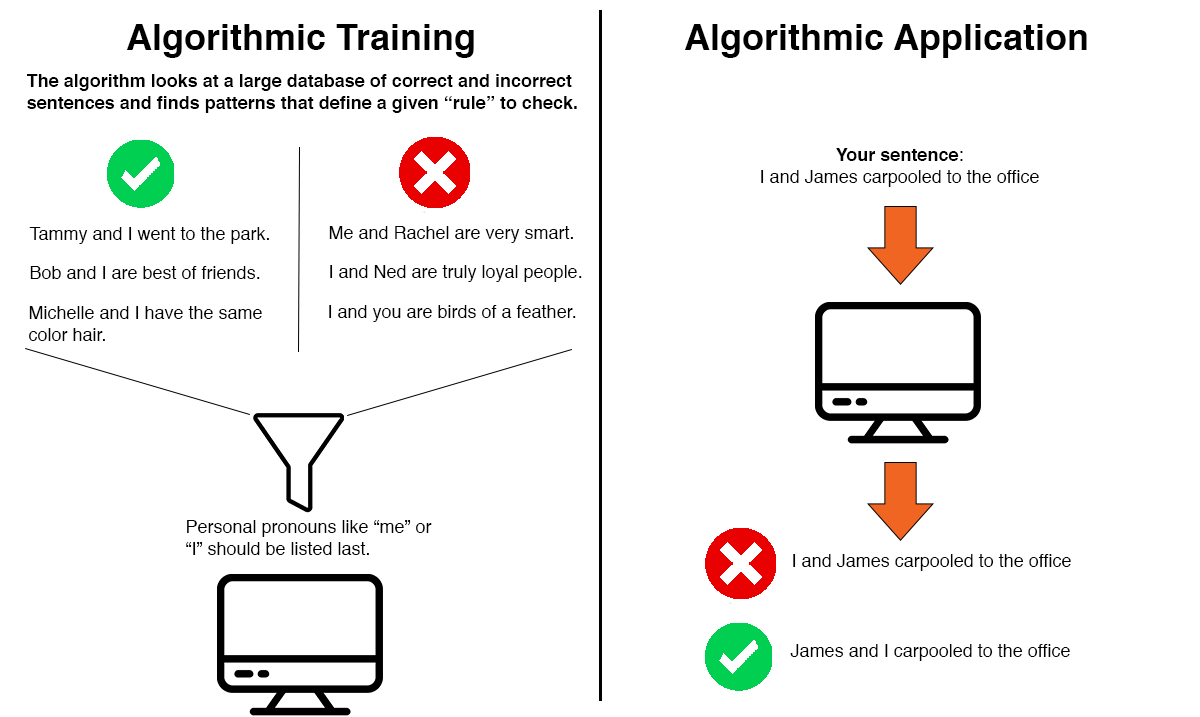

More advanced functions may rely on machine learning techniques. These involve “training” the program to recognize errors by providing it with a large number of examples. For instance, designers may have the program process 50,000 sentences that contain a certain type of error and 50,000 sentences that do not contain this error. Gradually, by processing many successive examples, the program develops an algorithm to recognize the linguistic patterns that signal the presence of the error. This allows the program to make educated guesses about the error when it encounters a new sentence.

More advanced functions may rely on machine learning techniques. These involve “training” the program to recognize errors by providing it with a large number of examples. For instance, designers may have the program process 50,000 sentences that contain a certain type of error and 50,000 sentences that do not contain this error. Gradually, by processing many successive examples, the program develops an algorithm to recognize the linguistic patterns that signal the presence of the error. This allows the program to make educated guesses about the error when it encounters a new sentence.

The diagram below illustrates how a paper checker can use algorithmic training to identify more complex errors:

These are, of course, greatly simplified explanations. The most important thing to remember is that paper checker apps are basically designed to recognize certain patterns in your paper so that they can identify errors and make suggestions about how to fix them. The ability to perform quick and uniform pattern recognition makes paper checker apps very powerful tools. However, it also means that they interpret writing in a fundamentally different way than the human brain does, which can occasionally result in blindspots.

How Can I Use Paper Checkers Wisely?

Re-read your work regardless of the app’s suggestions (or lack thereof).

This is the single most important rule for responsible paper checker usage. The other suggestions below might even be thought of as variations on this theme.

Even today’s most expertly-engineered paper checkers are not perfect. They may, for instance, occasionally misjudge “borderline” cases where strict adherence to grammatical rules doesn’t make sense. They may also falter in cases where the best sentence phrasing is determined by the author’s intended meaning or the writing’s context.

For example, one paper checker app that we tested struggled with the following sentence:

The app did not indicate any errors in this sentence. However, given the author’s likely intended meaning, the sentence is incorrect. The clause “walking down the street and talking on my phone” appears to modify the subject “dog.” Of course, dogs cannot talk on phones. The initial clause modifies an implied “I” subject. The sentence might be better written as follows:

In this version of the sentence, the “I” subject of the initial clause is clear. We call this type of error a dangling modifier error (see our resource on dangling modifiers for more information).

This is just one example of why it’s important never to mindlessly accept suggested revisions. Instead, review each revision individually to ensure the app’s suggestions make sense, and be sure also to re-read passages without any suggested changes.

Know the app’s limitations.

Think of this as a companion to the tip above. As you review your work, keep in mind that paper checkers can neither assess the meaning of your writing nor its persuasive strength. This means that they often have certain conceptual “blind spots” that can lead them to miss certain kinds of mistakes.

Here are just a few examples of things that paper checkers cannot always catch:

- Meaning-dependent grammatical errors (like dangling modifiers—see the example above)

- Certain sentence style issues (like a lack of linguistic clarity or a confusing structure)

- Certain paragraph-level issues (like providing redundant or unnecessary information)

- Poor word choice (like accidentally using “allegory” instead of “metaphor”)

- Certain kinds of misspellings (like spelling a source’s name wrong)

- Bad citation practices (like citing the wrong source, formatting a citation incorrectly, or placing a citation in a place that doesn’t make sense)

- Bad inferences (like extrapolating sweeping assumptions from limited evidence)

- Weak arguments (like a reliance on logical fallacies)

- Nonsensical imagery or metaphor (like saying “we are at the precipice of an important crossroads”)

- Improper formatting (like capitalizing every word of a source title in APA format)

Keep the context in mind as you interpret the app’s suggestions.

Grammar, style, and voice are not absolute sciences. Sometimes things like the purpose or intended audience of your writing can determine which choices are best. Thus, it’s important to consider these things as you revise.

For example, many paper checkers can identify the use of the passive voice and flag instances as possible errors. In general, this is good. Careless use of the passive voice can lead to dull or convoluted writing. For instance:

Clearly, “I won the race and the gold medal” is a more natural phrasing. In some cases, writers acting in bad faith can even use passive voice to obscure the true meaning of a sentence. See, for instance, this example:

How satisfying would it be to read this sentence in a statement from a CEO or politician in the midst of a scandal? Not very—it uses the passive voice to shirk responsibility for wrongdoing.

However, sometimes the passive voice is preferable because it emphasizes the object or action in the sentence, rather than the actor. For example, passive voice is often prized in scientific writing, where it is used to describe experimental methods with a detached, objective quality. For example:

Given the context, we would be right to interpret these sentences as more appropriate than ones like “I added the catalyst to a 250 milliliter Erlenmeyer flask.”

Ignore suggestions for passages that are formally or stylistically adventurous.

Ordinary writing rules tend to go out the window when an author is playing with style or form for artistic reasons. This means that it can be wise to ignore a paper checker’s suggestions for passages that do either of these things.

Examples are abundant in the world of poetry. Poets tend to value expression, rhythm, imagery, and feeling far more than grammatical convention. For example, here is the E.E. Cummings love poem Somewhere I Have Never Traveled Gladly Beyond:

If we were to accept every suggestion that a paper checker app might make for this poem, it simply wouldn’t be the same.

Plenty of prose examples also exist. Thomas Pynchon is an author who frequently uses run-on sentences to give his stories a disorienting, breathless quality. Here is the opening sentence from his novel The Crying of Lot 49:

Even non-fiction writing can play with form and style. Here is part of the opening to Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga (the actual paragraph goes on much longer). In this passage, Thompson uses a strategy similar to Pynchon’s to mirror the chaos that would accompany the notorious biker gang’s rides:

In any of the above cases, the author would be wise not to accept a paper checker’s revisions. These could rob the passages of their artistic character, and, in doing so, make them less effective.

Use caution if you are a multilingual writer.

The rules of English grammar, which can be complex, idiosyncratic, and arbitrary, are notoriously difficult to learn. Moreover, as writers move across professional settings, what counts as “English” can vary by discipline, community, and even by supervisor (see, e.g., Guerra, 2015). It is no wonder that people learning English as a primary or additional language can often be confounded. It is also no wonder that paper checker apps can subsequently appear very appealing to some multilingual writers.

Unfortunately, paper checkers can struggle with multilingual writing, which often does not contain the well-known patterns of error that speakers and writers more culturally-fluent in academic Englishes can exhibit. This means that, in certain situations, paper checker apps can actually make learning English more difficult by way of making improper suggestions.

Multilingual writers can help protect themselves by taking the following precautions:

1. Don’t assume that everything flagged as an error is incorrect.Paper checkers sometimes produce “false positives” when they misread the structure or syntax of a multilingual writer’s sentence. One app that we tested flagged an error in the following sentence from a multilingual student’s paper that turned out to be correct:

This sentence is grammatically correct. However, the paper checker suggested that the writer change “that” to “than” because it thought the writer was trying to make a comparison--probably because the app detected the preceding “more likely,” which triggered a rule for how comparative sentences are supposed to structured. Of course, this sort of comparison is not occurring here.

2. Don’t assume that all errors in the writing have been identified.On the other hand, paper checkers also sometimes miss errors when multilingual writing uses unexpected syntax or structure. The app that we tested missed an error in the following sentence from a multilingual student’s paper:

In this case, the app did not identify that “my Firefox” is an awkward, inappropriate phrase that would probably be better expressed as “the Firefox browser” or something similar. It also did not suggest that the writer use the more natural “Facebook interface” in place of “interface of Facebook.”

However, it did suggest that “interface” was confusing technical jargon that should be exchanged with a synonym. This is debatable and depends on the context--in a technical document or a piece of writing intended for experienced computer users, the term would probably be fine. The app’s suggested change was plainly wrong, however: exchanging “point of contact” for “interface” would invoke a different meaning and make the sentence nonsensical.

This is the version of the sentence the app suggested:

A better version of this sentence might look like this:

When paper checkers do identify flawed sentences, they may not always properly categorize the error because they have not grasped the writer’s intended meaning. This can lead to nonsensical suggestions. Here is another sentence we tested with one paper checker app:

In this case, the app suggested that the “the” before “most people need” may not be necessary. Of course, deleting this “the” would change the meaning of the sentence, since “most” is a noun here, rather than an adjective modifying “people.” A better fix would be to add a “that” after “most.” The writer might also change “people need” to “anyone needs” in order to make his or her intended meaning more clear. Of course, the writer should also add the article “a” before “Big house” and “luxury car” (the app did not make this suggestion).

This is the version of the sentence the app suggested:

A better version of this sentence might look like this:

In sum, paper checkers don’t always work well for multilingual writers. If you are a multilingual writer, rather than relying on a paper checker app’s feedback, consider booking an appointment with a dedicated tutor (see the final suggestion below).

Don’t substitute the app’s comments for human feedback.

Some paper checker apps not only identify errors, but also provide comments in “pop-ups” or marginal notes that describe the nature of the errors and give an indication of how to fix them. This is a powerful feature because it approximates the sort of feedback an experienced proofreader might give, lending an educational quality to the app’s services.

However, writers benefit more by seeking feedback from human readers like writing center tutors. Most writing centers (including the Purdue Writing Lab) direct tutors to use a dialogic approach to teaching writing that engages the writer’s grammar mainly as it pertains to whatever he or she is trying to express. The goal of this approach is to impart not only a sense of clarity, but also one of nuance, context, and rhetorical effectiveness to the writing. This is true even when a tutoring session focuses mostly on sentence-level concerns like grammar.

By contrast, paper checker apps, which lack a human’s ability to judge meaning, cannot ask the sorts of questions that tend to spur the greatest learning: “What were you trying to say here?” “What ideas were hardest to expressed?” “Why did you use this particular word?” They can give writers directions for fixing issues like grammar, but even when these directions are accurate, they are blind to the human qualities of the writing. For this reason, the feedback from paper checker apps can give the impression that improving one’s writing is merely a matter of fixing sentence-level errors. Of course, this is only one of many aspects of what constitutes “good writing.”

To sum up: by changing the way that writers approach proofreading, paper checker apps represent a potentially disruptive innovation in the world of writing. In order to reap the benefits of increased productivity, faster writing, and less worry, however, writers must be willing and able to judge their own writing in complex ways that even the most helpful apps cannot.

Reference

Guerra, J. C. (2015) Language, Culture, Identity and Citizenship in College Classrooms and Communities. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Icons

All icons in the diagrams above come via The Noun Project (Creative Commons License CCBY). Links and attributions for each icon are provided below.

Computer by My Toley from the Noun Project

checkmark by Jerry Checker from the Noun Project

X by Fardan from the Noun Project

dictionary by Smalllike from the Noun Project

squiggly line by Made by Made from the Noun Project

ellipsis by Gem Designs from the Noun Project

Funnel by Line Icons Pro from the Noun Project