World Englishes: An Introduction

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is “World Englishes?”

The term World Englishes refers to the differences in the English language that emerge as it is used in various contexts across the world. Scholars of World Englishes identify the varieties of English used in different sociolinguistic contexts, analyzing their history, background, function, and influence.

Languages develop to fulfill the needs of the societies that use them. Because societies contain a diverse range of social needs, and because these needs can differ across cultures and geographies, multiple varieties of the English language exist. These include American English, British English, Australian English, Canadian English, Indian English, and so on.

While there is no single way for a new variety of English to emerge, its development can generally be described as a process of adaptation. A certain group of speakers take a familiar variety of English and adapt the features of that variety to suit the needs of their social context.

For example, a store selling alcoholic beverages is called a “liquor store” in American English, whereas it is called an “off-licence” in British English. The latter term derives from British law, which distinguishes between businesses licensed to sell alcoholic beverages for consumption off the premises and those licensed for consumption at the point of sale (i.e., bars and pubs).

Such variations do not occur in terms of word choice only. They happen also in terms of spelling, pronunciation, sentence structure, accent, and meaning. As new linguistic adaptations accumulate over time, a distinct variety of English eventually emerges. World Englishes scholars use a range of different criteria to recognize a new English variant as an established World English. These include the sociolinguistic context of its use, its range of functional domains, and the ease with which new speakers can become acculturated to it, among other criteria.

The Origin of World Englishes

This section, which is not meant to be exhaustive, provides a simplified narrative of how World Englishes emerged as a field of inquiry.

1965

Linguist Braj Kachru (1932-2016) publishes his first journal article, entitled “The Indianness in Indian English.” In the article, he lays the theoretical groundwork for the idea of World Englishes by interpreting how English is nativized in India, delineating some of its unique sociological and cultural aspects, and showing that “Indian English” is a unique variety of English which is neither an American or British English.

1984

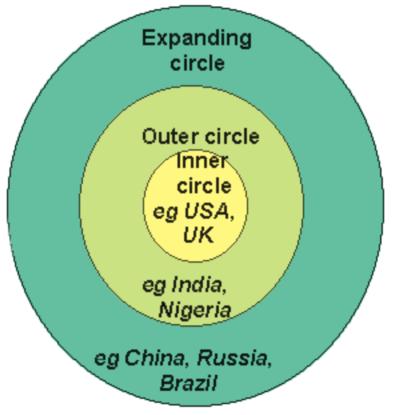

Kachru formally introduces the term “World Englishes” at the Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) Conference along with the global profile of English. Later, he proposes the three concentric circles model. Both papers are subsequently published.

Kachru's three concentric circle model. Image c/o Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons 4.0 License).

The inner circle refers to the countries where English is used as the primary language, such as the USA, Britain, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia.

The outer/middle circle denotes those countries where English usage has some colonial history. This includes nations such as India, Bangladesh, Ghana, Kenya, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, and Zambia.

The expanding circle includes countries where English is spoken but where it does not necessarily have a colonial history or primary/official language status. This includes nations such as China, Japan, South Korea, Egypt, Nepal, Indonesia, Israel, Korea, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, USSR, and Zimbabwe. Any country where English is regularly spoken (even in limited contexts—e.g., for international business) that does not fall under the first two categories is considered to be in the expanding circle.

The boundaries between outer and expanding circles can be blurred as the users of English in any of these specific countries may fluctuate because of the demographic shifts, economic motivations, and language education policy.

Kachru argues that it is important to view each variety of English in its own historical, political, sociolinguistic, and literary contexts. This concentric circle model does not only show the wide spread of English across the world, but also emphasizes “the concept of pluralism, linguistic heterogeneity, cultural diversity and the different theoretical and methodological foundations for teaching and research in English” (1984, p. 26).

Kachru also defines the quality of “nativeness” in World Englishes “in terms of both its functional domains and range, and its depth in social penetration and resultant acculturation” (1997, p. 68). A community acquires “native” English-speaking status as it uses English in broader a greater number of societal contexts. This process, however, is shaped by the historical role of English in the community (e.g., as the language of a colonizing force). It is this interaction between functionality and history that leads to the nativization of English in a particular society or population group. Consequently, Kachru argues, the English language belongs not only to its native speakers but also to its various non-native users throughout the world.

1992

Larry E. Smith contributes a chapter titled, “Spread of English and Issues of Intelligibility” to The Other Tongue: English Across Cultures, edited by Braj B. Kachru. Smith, in this chapter, mentions that since the global spread of English has been very rapid by historical standards, not all these English varieties will necessarily be intelligible to each other. Thus, he argues that the idea of English’s “intelligibility” should be thought of as a matter of its ability to be understood by a speaker and listener within the same speech community, rather than its degree to be understood solely by native speakers of English. He also proposes the following three terms to understand the interaction between speaker and listener: 1) intelligibility (word/utterance recognition), 2) comprehensibility (word/utterance meaning, or “locutionary force”), and 3) interpretability (meaning behind word/utterance, “illocutionary force”).