Using Citation Generators Responsibly

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This page describes how citation generator apps work to show what’s happening when a writer uses one. Then, it offers a few “best practices” for using citation generators. See also our similar article on "paper checker" apps.

Introduction

The citation generator is a relatively recent addition to the writer’s toolbox, but one that has already altered the practice of writing immensely. Gone are the days of painstakingly documenting every individual source by hand. Citation generators allow writers to generate citations in a fraction of the time this work once took. Some even allow writers to construct entire bibliographies on the fly that can be imported into projects with a few clicks.

Citation generators are, clearly, powerful tools. However, because citation generators have the potential to change the writing task so drastically, it’s important for writers to educate themselves about them. Used wisely, citation generators remove much of the tedium from the writing task so that writers can focus on the things that matter most—their ideas. Used unwisely, however, they can introduce systematic errors that the writer isn’t even aware of.

Thus, writers should remember that citation generators cannot (and should not) do their thinking for them. The rest of this guide provides information that can help you keep this simple principle in mind as you work.

How Do Citation Generators Work?

Citation generators are programs that turn information about a source into a citation that the writer can use in a project. Though many different citation generators exist, most follow this general process:

-

The generator receives information about a source. Usually, this comes from the user: he or she types the source’s author, title, publication date, and so on.

-

The generator processes this information according to settings the user has specified (e.g., the citation style and the medium). This usually means putting the pieces of information received in Step 1 into the correct order and applying the correct formatting.

-

The generator produces a citation (or set of citations) that the user can use. This usually takes the form of text that a user can copy and paste into a project.

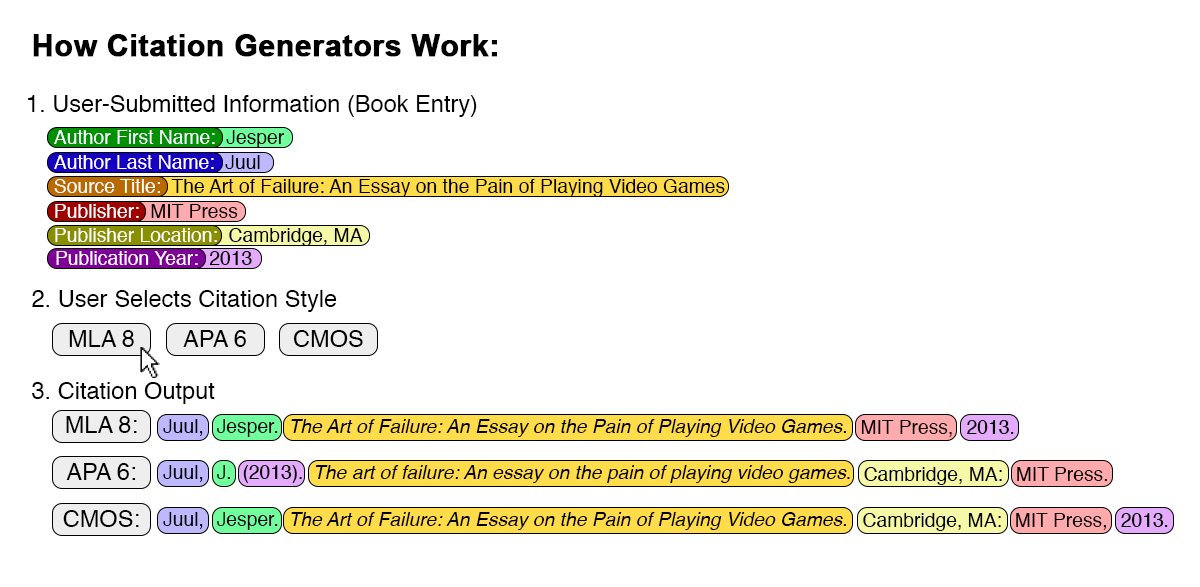

The diagram below illustrates this pattern.

Citation generators can be very sophisticated. Some offer additional features not described above. For instance, some generators can automatically locate sources in online databases and fill out entire citations with just a little bit of starting information—the source’s title, for instance. Other citation generators can automatically fix spelling or capitalization errors that the user makes when inputting the source’s information.

What’s important to realize, however, is that citation generators rely on the user’s input and follow set patterns. Citation generators cannot exercise any judgment of their own. They do not “understand” the task of citation in the way that humans do. They can only follow instructions given to them by their users and their programmers.

Thus, writers who use citation generators as if they were definitive authorities (rather than powerful tools) can expose themselves to problems. They may give citation generators inaccurate information (and thus receive incorrect citations) under the incorrect assumption that the generator can “sort out” any errors. They may use citations in ways that don’t make sense because they assume that as long as they have received the “correct” citation from the generator, any usage of this citation is valid. They may simply not think to double-check the citations they receive, and thus miss the occasional errors that even well-designed citation generators can make.

In short, relying entirely on citation generators rather than on one’s judgment as a writer can lead to errors. Below are a set of suggestions that can help you use citation generators wisely.

How Can I Use Citation Generators Wisely?

Make sure the information you input is correct.

No citation generator is perfectly insulated against user error. If you give a citation generator incorrect information, it will probably give you an inaccurate citation. Check your input information carefully as you enter it to ensure the accuracy of the final product.

-

Enacting this advice means doing some very obvious things. You should, for instance, check to make sure you’ve spelled the author’s name correctly (especially if it’s a name you haven’t encountered before). You should be aware, however, that subtler things like capitalization and punctuation can also matter. For instance, here is an MLA8 citation for a poem by E. E. Cummings:

-

Cummings, E. E. “anyone lived in a pretty how town.” Complete Poems: 1904-1962, edited by George J. Firmage, 1st ed, Liveright, 2016.

-

Note that, in this example, the unconventional lowercase title of the poem is maintained. You would want to ensure that a spellchecker (or the citation generator itself) has not incorrectly “fixed” the capitalization in the title before inputting that information.

-

Work from the copy of the source you have available, rather than from secondary information about the source (like a web page selling the source on an online store). It’s easy to miss minor details like edition number and editors’ names in the latter case.

Make sure you designate the correct medium, version, and/or edition for each source.

Citation generators can’t judge whether the information they receive about a source “makes sense.” They can’t tell, for instance, if you’re accidentally citing an academic journal article as a magazine article (and thus likely leaving out important information like volume number). They also can’t tell if the paperback and hardcover releases of the book you’re citing use different page numbers. Thus, to avoid unnecessary confusion for your readers, it’s always wise to double-check that you’ve indicated precisely the source you’re using (and not a source that’s “close, but no cigar”).

-

This advice is especially important if you’re using a citation generator that automatically searches for information about your source online. In this case, it’s crucial to make sure the generator has grabbed the correct edition, version (e.g., paperback vs. hardcover), etc. These minor differences can affect the page numbers and publication dates of sources, which means that getting this information wrong can lead to inaccurate citations.

-

Don’t forget that edited collections usually have at least one editor who needs to be credited in the citation in addition to the author of the piece you’re using. Keep this in mind if you’re citing a small work that appears in a bigger collection.

-

If you can’t figure out precisely what medium your source should be categorized as, consult the general formatting rules for the citation style you’re using. Usually, you will be able to assemble a usable citation simply by putting as much information as you have into the generic pattern your style specifies. Here are the links to the OWL's "Overview and Workshop" pages for each of the major citation styles:

Make sure to use reputable, accurate sources.

Citation generators work with the sources you give them. They can’t evaluate whether those sources are good or not. This means that it’s possible to use a citation generator to assemble a bibliography that’s technically flawless, but nevertheless useless. To avoid this, be sure to evaluate whether each source you use is accurate, reputable, and unbiased. Below are some questions to consider for each source. There is not necessarily a single "correct" answer to each of these questions (e.g., some emotionally-charged sources nevertheless contain true information, and some commercially-sponsored sources are truthful regardless of the source of their funding). However, considering these sorts of questions as you pick sources can help you make smarter choices.

-

Is your source peer-reviewed?

-

Is your source primary (i.e., does it come directly from the person providing the information, or is it mediated by someone else’s opinions and commentary)? If it is a secondary source, does it seem like the author is referencing primary sources when possible?

-

Does the source come from an organization with a vested interest in having an unbiased, authoritative reputation?

-

Does the source reference clear, unambiguous evidence? Is this evidence well-documented (for instance, in a bibliography)?

-

Does the source acknowledge a range of viewpoints even as it makes its own argument?

-

Does the source use emotionally-charged language or make broad generalizations?

-

Does the source come from a lone individual, particularly an individual without a reputation for careful, objective, or well-reasoned claims (or a motivation to preserve that reputation)?

-

Is the source commercially sponsored? Does the sponsor have a vested interest in the audience’s perception of the source’s topic?

For more help, consult the OWL's “Evaluating Sources: Overview” resource.

Double-check the citation you receive against a reference.

After you’ve finished inputting information and you’ve received a citation, resist the urge to copy and paste the citation into your document without first doing a quick check for accuracy. In the event that the citation generator has made an error (a rare but real possibility), you will be glad that you took an extra few seconds to verify its accuracy.

-

Pay particular attention to the way the generator has handled capitalization and formatting.

-

Note, for instance, that there are different rules for capitalizing titles in MLA and APA styles.

-

Note also that different styles handle numbering differently. Some, for instance, require page ranges to include all numbers in the start and end pages (e.g., 267-268), while others allow redundant numbers to be omitted (e.g., 267-8).

-

-

If you couldn’t find certain pieces of information (e.g., publication date) for your source, check to ensure that the information has been left out rather than being rendered as a generic placeholder (e.g., “[DATE]”).

Here, again, are the links to the OWL's "Overview and Workshop" pages for each of the major citation styles:

Make sure you cite each source in the text in a way that makes sense.

Remember that bibliographies are not the end of the story when it comes to citations. Citations must also be used in the text to indicate when information is being borrowed from a source. The good news is that many modern citation generators can automatically generate in-text citations once you’ve provided bibliographic information. The bad news, however, is that the correct usage of in-text citations is much more context-dependent than it is for bibliographic entries. This means that, when you use an in-text citation you’ve generated from a citation generator, you should check that you’re using it logically, rather than simply copying and pasting.

-

Here is an example. Suppose that you would like to cite a chapter by the author Jane Smith in a paper you’re writing about the history of pies. You input the source’s bibliographic information into the citation generator, you indicate that you’re using APA style, and you get the following in-text citation:

-

(Smith, 2015, pp. 122-128)

-

-

Now, you want to use this citation in the text, so you copy and paste it into a sentence where you’re borrowing from Smith’s source:

-

According to Smith, the world’s first pies were developed by the ancient Egyptians (Smith, 2015, pp. 122-128), while later innovations were spearheaded by the Macedonians (Smith, 2015, pp. 122-128).

-

-

The uncritical copying and pasting you’ve just done has led you to make a few mistakes in your citation. When you provide the author’s name in a signal phrase (like “According to Smith…”), you usually should not provide it again in the parenthetical. You also should not provide a source’s date multiple times in the same sentence. Finally, you should not provide vague page ranges when it’s possible to pinpoint precisely where you found the information you’re borrowing. The citation generator cannot judge the context of the sentence you’re using the citation in, so it can’t tell you to do any of these things. A much more sensible approach would look like this:

-

According to Smith (2015), the world’s first pies were developed by the ancient Egyptians (p. 123), while later innovations were spearheaded by the Macedonians (p. 127).

-

-

Note also that if you are using multiple sources by the same author, you may need to make special indications in the text. The citation generator may not tell you this. Here are links to OWL resources that can help you cite multiple sources by the same author:

In sum, when using citation generators, remember that they can do much of your work for you, but they cannot (and should not) do any of your thinking for you.