Poetic Feet and Line Length

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Poetic Feet

There are two parts to the term iambic pentameter. The first part refers to the type of poetic foot being used predominantly in the line. A poetic foot is a basic repeated sequence of meter composed of two or more accented or unaccented syllables. In the case of an iambic foot, the sequence is "unaccented, accented". There are other types of poetic feet commonly found in English language poetry.

The primary feet are referred to using these terms (an example word from Fussell's examples is given next to them):

- Iambic: destroy (unaccented/accented)

- Anapestic: intervene (unaccented/unaccented/accented)

- Trochaic: topsy (accented/unaccented)

- Dactylic: merrily (accented/unaccented/unaccented)

The substitutive feet (feet not used as primary, instead used to supplement and vary a primary foot) are referred to using these terms:

- Spondaic: hum drum (accented/accented)

- Pyrrhic: the sea/ son of/ mists (the "son of" in the middle being unaccented/unaccented)

The second part of defining iambic pentameter has to do with line length.

Line Length

The poetic foot then shows the placement of accented and unaccented syllables. But the second part of the term, pentameter, shows the number of feet per line. In the case of pentameter, there are basically five feet per line.

The types of line lengths are as follows:

- One foot: Monometer

- Two feet: Dimeter

- Three feet: Trimeter

- Four feet: Tetrameter

- Five feet: Pentameter

- Six feet: Hexameter

- Seven feet: Heptameter

- Eight feet: Octameter

Rarely is a line of a poem longer than eight feet seen in English language poetry (the poet C.K. Williams is an exception).

Line length and poetic feet are most easily seen in more formal verse. The example above from D.G. Rossetti is pretty obviously iambic pentameter. And Rossetti uses an accentual-syllabic meter to flesh out his poem with quite a bit of success. What most free verse poets find more useful than this strict form is accentual meter, where the accents only are counted in the line (although when scanned, the syllables are still marked off...it is just that their number is not of as much import.)

Take this free-verse example from James Merrill:

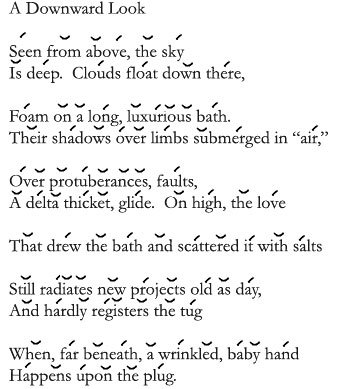

Free-verse James Merrill Poem

Things to note about this poem:

There is no any "set" meter in this poem, but the meter clearly plays a key role in its effectiveness. In particular it is worth noting the line that stands alone (line 7). Notice that Merrill moves toward iambic pentameter in line 6 and then sustains it through line 7. Here there is an inversion from the typical set-meter/variation sequence that is found in a lot of more formal poetry. Here the variation comes in the move into set meter, rather than varying from a set meter.

Just like establishing a visual pattern in a poem, establishing a meter creates expectations in your reader. Consequently, as with pattern, to vary that meter is to create emphasis. Some will say that your ear should be the first judge on these matters rather than your eye (looking at the scanned poem). There is probably some truth to this. Many poets will tell you that you should always read a poem out loud several times every time you get a draft done. If it doesn't sound good every time, there might be something that isn't working. This is where scanning the poem might come in handy; dissecting the lines and sculpting them until they sound better.