Meter and Scansion

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Meter

The bible of most poets today regarding meter and sound is a book by Paul Fussell called Poetic Meter and Poetic Form. Although some of Fussell's ideas are a bit outdated (namely, he doesn't deal with the visual elements of a poem), his approach is complete, concise and useful. Fussell defines meter as "what results when the natural rhythmical movements of colloquial speech are heightened, organized, and regulated so that [repetition] emerges from the relative phonetic haphazard of ordinary utterance." (4-5) To "meter" something, then, is to "measure" it (the word meter itself is derived from the Greek for measure), and there are four common ways to view meter.

- Syllabic: A general counting of syllables per line.

- Accentual: A counting of accents only per line. Syllables may vary between accents.

- Accentual-syllabic: A counting of syllables and accents.

- Quantitative: Measures the duration of words.

Of the ways of looking at meter, the most common in English are those that are accentual. English, being of Germanic origin, is a predominantly accentual language. This means that its natural rhythms are not found naturally from syllable to syllable, but rather from one accent to the next. There may be one, two, or three syllables between accents (or more, but this is a matter of debate). For this reason most English language poets opt to look at their own meter as accentual or accentual-syllabic. The former is the more common; adherence to the latter often leads an English language poet toward self-conscious verse, as their predictable rhythms are counter to natural English speech (not that it is impossible to create great verse with this technique, but there is a tendency for it to end up so).

To get a bearing on what these rhythms look and sound like, let's start with a method for writing out the rhythms of a poem. This technique is called scansion, and it is important because it puts visual markers onto an otherwise entirely heard phenomenon.

Scansion

There are three kinds of scansion: the graphic, the musical and the acoustic. Since the most commonly and most easily used is graphic, we will use it in our discussion. For a discussion of the others, I refer you to Fussell, page 18. To begin to look at graphic scansion, we first must look at a couple of symbols that are used to scan a poem.

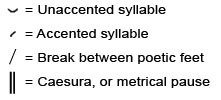

Scanison Symbols

Syllables can either be accented, meaning they are naturally given more emphasis when spoken, or unaccented, meaning they receive less emphasis when spoken. A poetic foot is a unit of accented and unaccented syllables that is repeated or used in sequence with others to form the meter. A caesura is a long pause in the middle of a line of poetry.

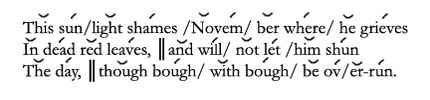

To show an example of these symbols, let's look at a poem written with the less common, the accentual-syllabic meter, in mind. Here are three scanned lines from Dante Gabriel Rossetti's "Autumn Idleness":

You can then see, when comparing the reading of the poem to the scansion marks, how they compare. These lines are taken from a sonnet and thus somewhat predictably written in iambic pentameter. They thus have five accents per line and their syllable counts are 10/10/10. The term iambic pentameter often comes up in discussions of Shakespeare or any sonneteer, but the meaning of the term is often mistaken or simply overlooked. Defining iambic pentameter helps us break down two important parts of meter: poetic feet and line length.