Tips for Writing in North American Colleges: Reasonability

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Medium Certainty

Academic conversations tend to value a "reasoned" style for writing. This style places special value on arguments that are objective, supported by strong evidence, and presented in a detatched, unemotional manner. Arguments that rely mainly on emotional appeals or that express the sorts of moods common in oral conversation, by contrast, are not usually as well-regarded (Schleppegrell 61).

One common way that Academic writers show that an argument is well-reasoned is to express their ideas with medium certainty. That is, they don't express their ideas in language that is too strong or too weak. Academic writers generally do not claim that their ideas are absolutely true.

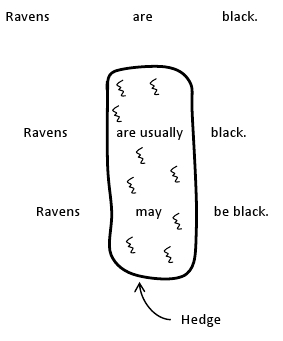

When academic writers use words to convey a medium level of certainty, this is called hedging. We use the word hedging to describe this practice because it compares writing to a hedge. A hedge is a kind of bush that is used as a barrier. In the same way, hedges in academic writing are used as barriers to protect academic writers from making statements beyond the level of their certainty. In other words, hedges help keep academic writers from saying things that are difficult to accept or are untrue. In the example below, the word “are” expresses high certainty, meaning that the statement must be true. But if someone in the audience can provide one example of a raven that is not black, then the writer has been proven wrong and their argument will not be accepted as a valid argument. However, the words in the hedge diagram protect the writer from expressing inappropriate levels of certainty. The words “are usually” express medium certainty. If an audience member does find a raven that is not black, the writer’s argument may still be accepted because “usually” means that “most, but not all” ravens are black. This also applies to the word “may,” which expresses low certainty.

In general, medium certainty is preferred in academic writing. Examine the sentence below to see how the engineering writers might express medium certainty of their idea:

This method must always produce superior results.

The use of “must” and “always” suggests that the writer knows with high certainty that their claims are true. It also suggests that the audience does not have a choice in accepting the writer’s ideas, because the writer indicates with their word choice that their idea could not possibly be wrong. Therefore, the writer is assuming a higher status than the audience.

This method could produce superior results.

The use of “could” indicates that the writer has very low certainty of their ideas. This may suggest the writer is of lower status than the audience, because the writer does not seem to be confident enough to make a claim for the audience to evaluate. The audience may not accept the writer’s ideas. However, it is better to express ideas with lower certainty than with higher certainty because lower certainty respects the audience’s choice to accept or reject your ideas. A writer expressing high certainty may appear to be creating an unequal relationship with the audience, which would make the audience less likely to accept their argument.

This method will likely produce superior results.

The use of “will” and “likely” creates an equal relationship with the audience. As a result, the writer’s idea could be accepted or rejected by the audience. But the writer has used the word "likely” to indicate that the idea is debatable. This means that the writer will try to convince the audience through reason and evidence (Schleppegrell 61). Below are some common words used to express different levels of certainty:

|

Low Certainty |

Medium Certainty (prefered in academic writing) |

High Certainty |

|

might could possibly may |

probably will should usually likely |

is must certainly always |

Adapted from Halliday & Matthiessen (148, 615-623)

Declarative Sentences

Academic writers show their knowledge and express ideas primarily through declarative sentences. Declarative sentences are sentences that express a statement or an assertion (Schleppegrell 58-59). For example, the sentence below is a declarative sentence:

Neutrinos, however, are unfazed by a mere mile of solid ground: on the average they could travel through a light-year of lead. (Arny & Schneider 321)

The sentence makes a statement about the nature of “neutrinos,” which are a kind of particle. The choice of a declarative sentence by Arny & Schneider allows them to convey ideas about neutrinos to the reader directly. Other kinds of sentences in English include imperative sentences and interrogative sentences. An imperative sentence makes a command or direct request of the audience. An interrogative sentence asks a question or requests information from the audience. Imperative and interrogative sentences are not common in academic writing, but they are common in speech.

However, sometimes academic writers do use interrogative sentences. But in these cases, the writer is not asking a direct question of the audience. Instead, interrogative questions are generally used in academic writing to provide a rationale for information or to show a line of reasoning (Schleppegrell 60). The example below shows how Arny & Schneider continue their reasoning regarding neutrinos by using an interrogative sentence:

The writers restate the previous sentence’s idea regarding the “unstoppability” of neutrinos. Then they use an interrogative sentence: “How are neutrinos detected?” They pose this question to provide a rationale for their next sentence, which explains how scientists detect neutrinos. In general, academic writers use interrogative sentences sparingly, and only for specific purposes like reasoning and providing rationale for information.

References

Arny, T., & Schneider, S. (2010). Explorations : An introduction to astronomy (6th ed.). Dubuque, IA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Halliday, M., & Matthiessen, C. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar. (3rd ed. / M.A.K. Halliday ; rev. by Christian M.I.M. Matthiessen.. ed.). London : New York: Arnold ; Distributed in the United States of America by Oxford University Press.

Schleppegrell, M. (2004). The language of schooling : A functional linguistics perspective. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.